1 - Cabrini Hospital

‘Inside you’re rotten. Inside you’re no good.’

Those words came from a colorectal surgeon at Cabrini Hospital as he assessed my stomach. That day he wore a pink fur coat and fake teeth—a case of poor timing really: he was on his way to an Austin Powers-themed party.

‘Any more pain in that gut of yours,’ he said, ‘and I’ll have to cut you.’ When he swivelled the examination light away, I felt a whole-body chill, like a corpse in the morgue. I asked whether stress could worsen my condition. He said, ‘Yeah baby, yeah... I’m sorry, that was… but yes: stress and I’ll cut you.’

That night, aided by a cocktail of pain meds and anti-anxiety wafers, I tried to submerge my stress like a balloon in water. Yes, the painful infection in my abdomen had worsened, but it was the old man in the next bed that caused me to worry the most: he was dying, and it was a loud death.

The old man was cancerous and senile. He spent the last two days on loudspeaker yelling at his son, reciting the same dog-eared script: ‘John, you weren’t good enough.’ ‘Dad, my name is Jared. You are John, remember?’ ‘Never good enough, John—a disappointment.’ But come nightfall, he called only for God. And for some—John included—death is orgasmic: an overwhelming bodily sensation. He gripped the bedsheets and moaned at his end. He climbed like a skeleton from the dirt one last time and expired. His soul left. His body, however, floated in the sparkling cosmos of warning lights and monitors.

Poor John, I thought. But that is my end too, if not now, then later. Either way, what a waste I will have made of my life.

In the end, I was hospitalised for four nights and released. I don’t know why I was spared, or indeed why I have been spared across my thirty-five years. Luck is unearned, by definition. I would have to return for further tests, but apparently they could wait. I have a brother in America, so I asked the surgeon if it was safe to visit him for a holiday. He said it was a great idea. ‘Live a little—have sex,’ he said, ‘But under no circumstances can you stress. Stress and I will gut you like a fish.’

Within forty-eight hours, I had booked, packed, and then flown to the United States of America. Three weeks of relaxation, rejuvenation, and redemption—that was my plan.

But I only made it as far as the Customs and Border Protection interrogation room at LAX before the threat of deportation, and stress, loomed.

‘Pretty strange for a solo male traveller to have two large bags,’ said the first CBP officer. He stood so close our noses docked, side-by-side; our facial hair rubbed. ‘Would you concede it’s strange, you freak?’

‘It… it surely depends on what the man’s purposes are.’

‘Don’t try to fuck us, Sir,’ said the second CBP officer. ‘We know what’s in your bags.’ As per the training manual, he stood in a combat stance behind the waterboarding table, his M4 rifle pointed at my temple.

The contents of my bags were complicated to explain. I probably should have considered my spiel prior to arriving, or at least before the CBP supervisor entered the bright room. It was too late now, though, because she was here, and fast approaching.

Still, I tried: I searched my mind for a compelling reason, but all my thoughts were noise, like a foreign film without subtitles. No good explanations came. Perhaps there are no ‘good’ explanations for an entire suitcase of condoms, ribbed or otherwise.

‘What’s this all about, Miller?’ she asked the first officer. ‘I’m on the clock.’

‘This freak intends to fuck his way across our great nation,’ said Miller.

Miller handed his supervisor my folded map of America like it was covered in faeces.

On the map, red arrows pointed from California to Texas and then up the country’s gut. Next to each arrow was a crude drawing of the female form: memories of an ex walking naked to the shower, toothbrush in her mouth… I had forgotten the drawings momentarily, and seeing a woman inspect them—a woman with the power to deport me, mind you—was cause for what, under other circumstances, I would call ‘stress.’

‘Is that true?’ she asked. ‘Do you intend to fornicate your way west to east, then south to north?’

‘The condoms, ah yes,’ I said. ‘Merely a precaution, Ma’am, to protect the women of this country... Not from me though; I’m no threat, certainly not a sexual predator, or any kind of predator, though I have been known to attack a few chicken wings from time to… Listen, it’s all about the STDs… which I don’t have, and nor do you.’

The supervisor, Officer Belinda Bourke, dropped the map in an evidence bag and sanitised her hands. I took this as a bad sign.

‘Says on your form you’re visiting your brother in Minnesota,’ she continued.

‘He’s innocent.’

‘We’re all sinners under God, Mr Skelton, but your brother is different; he’s like God.’

‘No, no. I just mean he’s married, and if I ever get married, I’m not wearing condoms—that’s all, no more. And… and I assume my brother, being of my flesh and blood and DNA, probably feels the same. Genetics are real. Hereditary traits exist. We are not blank slates as some philosophers might have you believe. Attitudes to condoms might fall into the nature, rather than nurture, category; that’s all I’m saying.’

Like a sword, Officer Bourke unsheathed her studded baton.

‘Or… he might love condoms,’ I continued. ‘They do help you last longer. Many times I insisted to a one-night stand that we should be “safe” when really my concerns were around peak performance. Kobe Bryant didn’t play barefoot, after all, and shoes are just condoms for the feet. I’m rambling, listen: my brother is a normal man. He’s married to a wonderful, patriotic American, not a native American but still a… you know what I mean… How about this: Since the dawn of time, safety has plagued–’

‘And the second suitcase, sir?’ interrupted Officer Bourke.

Oh, no–the second suitcase. I forgot the second suitcase—the ‘industrial quantity of Viagra’ suitcase. Pharmaceuticals could certainly trigger deportation.

My reasons for the pills needed to be stamp-ready or my trip would be over before it began. The best strategy, I believed at the time, was the truth; I was raised not to lie.

‘The reason for the Viagra is simple,’ I declared. ‘Many women in this beautiful country make me sick. No, wait, that didn’t come out right. Look, what I mean is… is that without “assistance” I’m worried I wouldn’t be able to perform due to the… the hideous appearances of…’

Officer Bourke lubed her studded baton.

‘None needed for you though,’ I said. ‘Personally, I like the eyepatch. In fact, with you, Viagra might do more harm than good. I might explode, as in a heart-attack, not premature ejaculation–or God a bomb, not like a bomb. No bombs here; none hidden in my anus (or is it ‘up’ my anus?). What I mean is I once saw the breastplate of a man in Napoleon's army with a cannonball-shaped hole through it. That’s how attractive I find; most men would find… heterosexual men of course! Gay men find attractive what they find attractive, and I embrace that. We should all experiment. Science is about experimentation. We wouldn’t have the toaster or bridges or Wi-Fi without experimentation. Suck away, I say. Sexuality is a many-headed snake. Hell, just between us, I find all sexuality confusing. I once saw my own hairy ass in a mirror, thrusting away during the act; it sickened me. Since then, I don’t understand heterosexuality or homosexuality. I killed my own erection; it was an erection suicide. I even left a note: “If you’re reading this, then I’m flaccid.” Do you understand? I’m repulsed all the time. Can we disgust ourselves that much? Could mirrors and selfies drive us extinct, or create a natural selection process for vanity? Could our DNA on some level be like: “Ey meng, we gotta stop this bloodline, Holmes.” I like to do accents, but I mean nothing by it, Officer… Ramirez. Sorry, what was your question?’

Officer Bourke turned to Ramirez, the officer with the pointed M4. ‘Why are his eyes doing that?’ she asked.

‘Bug-eyed, ma’am,’ he said. ‘They tell a story I ain’t wish to hear. Maybe I should shoot him.’

‘Miller, what do I always say?’

‘When it comes to border security,’ said Miller, ‘there’s no room for maybes.’

‘Exactly. Go fetch the rejecting stamp.’ Before Miller reached the door, however, she called out. ‘Miller wait,’ she said. ‘Bring both stamps. Suppose we cut this freak loose and see if he ends up on the news.’

‘Officer Bourke, the Merciful.’

‘Maybe,’ she said, and all three cackled, and a laugh track played, and Miller moonwalked out the blood-stained door to fetch two stamps—two fates—and I collapsed into a mental ad-break: Brain, we’ll be right back...

2 - LAX

Some age past thirty blacking out became a common occurrence—from drinking sometimes, but mostly not. Months before the hospitalisation I spoke to a professional to understand the cause. ‘Stress,’ she said. The only problem with her diagnosis—and I explained this at the time—was I have no reason to stress, or at least no right…

My life is simple. I’m no multinational corporation or circus for spiders. There’s no wife to disappoint, no children to lose, no mortgage hugging me like a boa constrictor. My only challenges relate to restraint: truths not said, steps not taken. I bathe in bureaucratic waters and doggy paddle. I work short-term contracts. I live in the now; tomorrow is dull; tomorrow is pointless. Restraint and futility, these are my shackles.

But it’s an insult to the impoverished, the diseased, the business owner, garbage man, mother, soldier and priest to call those shackles ‘stressful.’ So, you are wrong, I said. I designed my life so I cannot be hurt. Data points to a flatlined fate. I’m insulated from everything, but yes, I feel a lot, maybe too much, and you call that stress—bullshit. It’s like you’re telling me there’s no such thing as a low-stakes life.

The psychologist told her receptionist to cancel all appointments. ‘Mr Skelton has collapsed,’ she said. ‘Nope. No cash in his wallet this time... Fine, the Myki is yours… Susan, I will never let you in the MCC.’

Later, I awoke in a wheelchair being pushed through the LAX terminal.

‘Where’s my condom bag?’ I asked the man pushing me towards the exit. ‘Is it safe?’

‘Easy. Calm down, Brother,’ he said. ‘Nothin’s safe in Los Angeles. You gonna learn that fo’ yo’self.’

‘No one’s poking holes in them, I mean. Condoms are nearly useless after that.’

‘Friend of mine got full of holes last year. Full o’ holes, like Swiss cheese…’

Los Angeles proved to not be the health spa I imagined. On the flight over I pictured a beach and a vibrant boardwalk. I expected sunshine and laughing women. There’s nothing sweeter than laughing women (except Ribena, but according to Aristotle that’s too sweet). Instead of the finer things, though, I found trouble.

The cab that drove me from LAX fled with a tyre screech at the mere sight of an approaching local. I, by comparison, was relaxed, if a little groggy. I saluted and waved.

I blame jetlag for mistaking the local as the hostel’s doorman; hostels don’t often have doormen, and the hostels that do, usually have clothed doormen, or doormen with hidden pubes, or at least doormen with trimmed pubes. Another option is pubes shaved into the logo: ‘Welcome to the Venice Beach Hostel. As I show you to your bed, please marvel at my V-shaped pubes.’ That might be a nice touch. ‘How was your flight?’ he asks as you nod at his pubes. ‘I, too, find flying to be rather stressful, flying on meth, that is.’

In hindsight, the mix-up was on me. The only resemblance between the local and a card-carrying doorman was proximity to a door. At a stretch one could argue they both wear hats, but in the local’s case it was technically a garbage bag, and not a very nice one.

Ignorant of the truth, however, I passed him my Viagra bag and he shoved me in return. I muttered something about professional standards, so he reached into his anus (‘up’ his anus?) and removed a blade.

The anus blade looked like an excavated, muddy fragment of burst pipe. He displayed it like a construction worker would to a site manager. ‘Please tell me that’s not an indigenous artefact. Please tell me that’s an anus blade and not an artefact. There’s no more budget for artefacts–we’re ruined.’

‘You’re gonna fucking die, man.’ he said. ‘What you gonna do about it?’

A cursory glance down Venice Boulevard, with its homeless tents and graffiti, suggested the city shared this outlook: we are going to die, so what should we do? It’s a Google Calendar rather than Excel question.

The answer, collectively, appeared to be: destroy ourselves. The city, in that sense, reminded me of my digestive tract. It was like a theatrical rendition: the dealers, violent youths, homeless, addicted–all just Hollywood actors playing the parts of unhealthy bacteria. Their filth was a costume, knitted by their mothers. They searched the dim crowd for their father, Oscar. LA is a school play gone wrong, a biology lesson. Even my surgeon was there, high on a billboard, his scalpel pointing to the human anatomy: ‘Are you injured? Do you know bad bacteria threaten the good? Do you know we must kill the bad bacteria? Kill the bad bacteria TODAY. Do it now. Kill the man before you. Stop holding back. Cleanse the world. Call 1-xxx-xxx-xxx.’

‘What you gonna do about it, Motherfucker?’ he repeated. ‘What… are… you… gonna… do?’

I considered his question but the more I listened to my head, the more stress I felt, and the more I followed my heart, the greater the pain. And I’m allowed neither: stress nor pain.

Sure, there were steps to take, definitive, assertive steps, but those too were prohibited. Even when provoked, the outcome is mine: good fortune carries with it accountability. ‘To whom much is given, much will be required.’ What about fear? Let fear be your compass and you’ll never be trapped. Run, run, run and hide little rabbit. But what I felt—what I so often feel—is not fear, not of another, anyway.

In the end, I found no good option. A part of me choked forward like a guard dog while another tugged on the chain. Soon the chain will snap—for me and collectively—but today restraint won out. I apologised to the aggressor (He’s lived a hard life) and I backed through the hostel gate to safety.

3 - Venice Beach, Los Angeles

I’m not sure how many billable hours or timesheets worth of life passed in LA. My stay was supposed to be four nights, but I left on either the second or third, and I left in a hurry.

The cause of my departure, or I should say ‘proximate cause,’ was a fellow hostel guest who tried to rob me. The other contributing factors were my deteriorating physical and mental state and the hostel itself.

After my run-in with the fake doorman, the pain in my abdomen worsened. It felt like my intestines were plastic-wrap and someone had poked a hole through with a pen. I was lunch ham (which is only 70% ham, by the way). I spent my days limping between the kitchen faucet and bed. And the hostel itself did little to calm my nerves.

The business was going under, so staff had been let go. Only an external cleaner came twice a day: once to clean and once to shit on the floor (that’s called ‘business development’). Luggage went unprotected. Rats ruled sans fear. They performed their own HBO drama of conquest and dynasty on the floorboard stage. You’d wake to a dead rodent by the loo: an heir, a rebel, a scorned lover, perhaps. At night, the doors flung wide open and only a gate with a four-digit passcode protected guests from outside. Were the shadows creeping by your bed guests, owners, thieves, or worse? No one knew. You had to be vigilant to protect what mattered most. I slept with the condom bag between my legs.

Sleep is not the right term though, because I was alert. I lay in wait, pained and tired, yes, but ready.

The woman who tried to rob me must have assumed otherwise. It was late: hour of the rat. From her vantage, my face was lost in the abyss cast by the empty top bunk. So, believing I was unconscious, she ran a hand over my mattress. Her fingers slid into my breast pocket, seeking cash or a wallet. Nothing came up. With each touch she grew bolder. She pulled back the blanket, folding it upon itself. Everything was measured, steady. Her soft hand caressed down my side to my jean pocket. Her fingers burrowed in–nothing. I wondered if she questioned why I was dressed, boots on, ready. I wonder if she considered it might be a trap…

The thieving shadow, I knew. We met earlier that day when she went berserk after I explained there were no staff to manage her check-in. ‘Yet here you are,’ she said, ‘all checked in. Interesting.’ ‘I’m not checked in,’ I said. Her eyes scanned me from boot to brain then flew across reception in search of evidence, proof of the elaborate plot against her. The world had it out for her, she believed, and I was its spokesperson.

‘You do know I could rob everyone here?’ she said. Her giant blue backpack thudded to the floor. Her arms stretched to the ceiling. Something in her birdsnest of hair moved, a rodent perhaps (had they gotten to her already?) ‘I could steal everyone’s shit. Fuck this place.’ Her missing front teeth turned her cackling into a train whistle. ‘This place ain’t shit,’ she said. She kicked the computer off the desk, tore a book from the case and pitched it at the glass door; the book dropped like a dead bird. On the cover, a man with a moustache covering his entire mouth gazed back. ‘I could do anything—anything! And maybe I fucking will. No one ever fucking listens to me. They’ll be sorry. They will.’

As she yelled, a stab in my gut caused me to grimace. ‘Why you looking at me like that,’ she said. ‘Tell me. Oh, don’t bother; I know. I see. Very interesting,’ she said. ‘He thinks we’re crazy. Very interesting.’

In the end, I suggested she find a spare bed and set up there. ‘Oh, I will. Don’t you worry.’ That bed turned out to be next to mine, in the otherwise-empty rear room.

Under other circumstances, what an ideal set-up! We could have shared the night: shushing, giggling, touching, kissing… In the morning, to escape the judging eyes of other guests, we could have shared a crack pipe under your favourite bridge. You could have shown me where the pigeons live. We could have fallen in love.

I would have spoiled it though by getting too political, and your stash would run dry, so we would part ways, but we are soulmates so I would rush to the depot as the bus pulled out, play your favourite Jamaican hip-hop beats from my iPhone, call your name (‘Starchild’ or whatever), collapse to my knees in the heavy rain, and shout, ‘Remember me each time a pigeon flies,’ and crying, but knowing in your heart you had to move on, to migrate with your brethren birds, you would cut one of your matted locks, feed it through the bus window, and it would land on the concrete like a brown nugget in the toilet of our love. Flush. It wasn’t to be, not for us…

When her thumb brushed my earlobe, I seized her wrist. Instead of trying to pull free, she froze.

There was a voice in my head that asked, ‘But why is she robbing you? Think of the socioeconomic forces that drove her to this?’ ‘I know,’ I replied, ‘but what do you expect of me: to lie here, to be voluntarily picked at like a corpse. Do you take me for a saint?’ ‘But you must be, because you have lived an easy life. She did not choose to rob you, but you can choose to let her. Let them all take, destroy, corrupt. Do you know what happens to the world if people like you lose their restraint? Just collapse.’ ‘Fuck that. I’m done with that,’ replied another voice.

Still holding her wrist, I shifted forward out of the abyss. My features emerged to her as blocks of grey colour, like a film negative.

And it’s a strange head to look at, my head. The square jaw and full cheeks are at odds with the tiny brainbox and thinning hair—egg-shaped. And it was that bulky chin that I thrust into the light to exacerbate my misshapenness. I felt her tug as she tried to flee, so I gripped tighter. I was not done.

Tensing hard, I contorted that bulky slab of facial muscle, stubble, and sinew I call a face into a wide smile. The woman bleated like a scared goat. Staring into the abyss, she saw the face of a lunatic, while I saw a scared little girl. Then I released her wrist.

The woman fell off my bed, shuffled backwards on the boards with the rats and mess, felt in the dark for her bag, and ran to the night. In the end, she took nothing from me, and for a brief moment I was happy.

But the voices soon returned: ‘Couldn’t you have done things differently?’ ‘Me–she was robbing me.’ ‘Then let her rob you; let her slit your throat; she’s had a hard life.’ ‘But that would make my life hard.’ ‘Then you’d be beginning to make things even.’ ‘That makes no sense.’ ‘Who said you were entitled to sense?’ The argument climbed, louder and louder, like two stubborn parents, until it was a stadium roar. I clasped my ears but it was no use. I, too, needed to move, fast. I fetched my bags and left the cursed hostel.

4 - The Road

From a gas station west of Dallas, I posted a Google review for the hostel: ‘Two stars–great location, horror movie atmosphere. Rats want your condoms.’

That day I was headed for Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. I opted to drive all the way to my brother in Minnesota because I needed time and space. He couldn’t see me like this: half-crazed, hell, full-crazed.

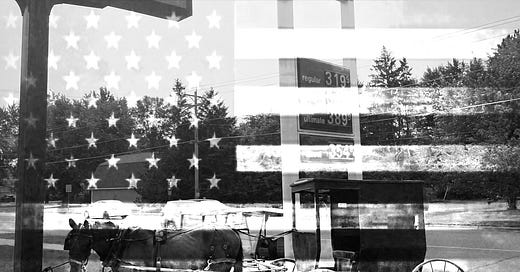

Beyond the illuminated pump bay, the first light climbed but it cast no oil painting. The landscape was instead a vague, boring place with no landmarks or life, just floating numbers—the cost of gas.

That also sums up the arteries running north through Oklahoma, or at least my experience of them. I rented the car in Los Angeles mere hours after making that poor woman shriek, and having driven basically since then, my perception of time and place were off, but deliberately so, like wearing sunglasses at night. The days became a flowing blur. I wanted no part in life, so I acted strange until it was beyond my comprehension.

The week on the road came in strange flashes. I was headed west, from Broken Arrow to Arkansas. I was inside another gas station, a crowded phone-booth of a place. An elderly woman had taken my hand in hers. Her smile was dry and ancient, her pale eyes, knowing. The last drop of moisture from her body she stored in a vial around her neck: drink it and see all she has seen, which is too much for most. She is the sole possessor of soon-to-be lost wisdom; we all are in the end.

‘Let me get those for you,’ she said, nodding to the counter, to my expensive coffee, pack of cigarettes, and paper. ‘Jesus spoke to me. He told me you’re in need of help.’

Outside, a man in overalls lowered the old woman into a rusted truck. I stood by my shining Ford Mustang convertible, smoking. The man in the overalls glanced at me, then faced the hot cement.

In Missouri, I conducted a condom stocktake on the side of I-44. The condoms were arranged on the roadside in piles of ten, all checked, all reflecting in the iPhone torchlight. The car was idling.

Everything felt urgent: life, the stocktake, death. I imagined my father then: his timid eyes, resonant voice, big heart, twisted tongue. He’s a container for contradictions, a complex man. I, too, yearn to be complex. I thought of my father because he was once a stocktaker, before calculators. He still counts aloud in a rhythmic chant. He’s saying numbers but it flows like a jungle beat: ‘ten-ta-da-ten-ta-da-ten-ta-da…’

I peeled a condom off the gravel, held it as tribute to the canvas of stars, and wept. If my father had worn a Durex I would not be here. If his father wore one, neither of us would be. I imagined how far back we go: it’s all the way back. We are from the beginning of time, he and I, father and son. That was southern Missouri.

North, outside Kansas City, I stopped at a waterpark. Two armed guards patrolled the perimeter in bulletproof vests and balaclavas. The guards explained a fourteen-year-old girl had recently been shot dead at the park. A police presence was deemed ‘too inflammatory,’ so heavily-armed goons were hired to manage tensions. ‘So smart, so dumb,’ I said. ‘Who cares about inflammation? She’s dead–let’s burn the world down.’

‘What the fuck did he say? Hands up. Spread 'em—now.’

When the guards checked my bags they found condoms and Viagra. I was apprehended.

Chris Hansen, host of To Catch a Predator, led the subsequent interrogation. He asked what my intentions were at a waterpark for children. I said I was trying to escape the heat. ‘Just as I suspected: a fugitive.’ He smacked me in the mouth with a flashlight. ‘As in hot weather,’ I said, and Hansen replied, ‘Oh, that checks out.’

Hansen wiped the sweat from his brow, left the interrogation lamp’s glow and paced to the window. He created a hole in the slat blinds and squinted at the punishing sun. He asked what it was doing here. He wanted to know the sun’s intent. He had the chat logs. He knew. There were police behind the moon, waiting.

That evening, west again to Lawrence, Kansas, I sat in the gutter of my hotel as a lightning storm approached. I listened to the rainsong beyond the covers and smoked an entire pack of Camel cigarettes.

Back home I’m no smoker, quite the opposite. My father had lung cancer from smoking. The risks, costs, damages–I know them well. I attend anti-smoking rallies. I hand out pamphlets. ‘Just remember,’ I tell the kids between songs at the Just Say No camps, ‘cigarettes are cringe AF.’

But here, in America, the packets are colourful and branded with cool pictures of camels. How could I possibly say no? I’m Australian: I’m suggestable, eager to destroy myself, yes, but always within the net cast by the government of the day.

That is our notion of freedom, and I accept it. Cigarette packs should be ugly. I just wish we evenly applied the logic. Why only villainise smoking? You can buy colourful alcohol bottles. Gambling companies use celebrities in their ads. In big bold letters consulting firms claim you will change the world.

I know about consulting firms because until recently I was a consultant. I say ‘recently’ because I was fired after (for) sending a bomb threat over Microsoft Teams at a ‘Get to know the CEO fireside chat.’

The next day a courier collected my laptop, headset, company-branded picnic rug, coffee cup, hat, and dildo (modelled on the CEO I threatened). In total, the merch filled two dildo-high boxes, and I wonder, looking back, if I would have even applied for the job if not for all the kit, branding and spin.

That’s why consulting firms should be subjected to the same regulations as cigarette companies: they hook young people under false pretences—changing the world rhetoric, free pizza… It’s a health hazard. WARNING: Consulting may cause loss of human soul… The picture shows a chair-shaped, crying humanoid.

Like smoking, the habit will be shunned: ‘Sorry, no PowerPoints allowed. There’s a PowerPoint section outside, in the rain.’ Folks who recently quit but get the itch after a few pints can wander out. ‘Hey Mate, got a spare slide I could borrow?’ ‘Sorry Bro, all out.’ ‘But I can see you’ve got a slide there on the five pillars of success, with little icons atop each success pillar.’ ‘Í said “I’m out, Brother,” now fuck off.’ And when he turns you king-hit him. His skull drums the concrete and you wind up in the mouth of a polished news presenter, your life immortalised in a story about consulting-fueled violence. And his mother is crying over a picture frame on A Current Affair, and don’t you know it’s his LinkedIn photo, and don’t you know that’s his legacy—that’s it—and at his funeral they’ll only say one thing: he was a hard worker, our Jim.

Did Jim change the world in the end? ‘Fuck Jim, he’s dead—that’s 0% billable.’

This type of musing, Grateful Dead songs, and the odd chat with a passing stranger, covered two thousand miles, and by the time I reached Atcheson, Kansas, I felt better than I had in a while.

That’s the thing about long drives: loneliness starts to make sense. Out here you’re lonely for a reason. You move too quick for connection and your soul knows it, so you relax. You don’t stress about other people. They hate you, who cares? Trust the miles.

As fate would have it, an annual festival—a celebration—was underway in Atcheson. I parked behind a silver food truck and joined the crowd. I felt ready to ‘live’ as the surgeon suggested, and to that end there were dozens of women in town. For now, though, all I’ll say is this: I left my condoms in Atcheson, every single one, and you can probably guess how...

5 - Atcheson, Kansas

The Aaron Eckhart Festival is held annually in Atchison, Kansas on a hot weekend in July. To celebrate the Hollywood actor, Aaron Eckhart, Vendors sell drinks and snacks on the main strip while a mariachi band plays on a low stage. Their tunes broadcast down the industrial-looking mainstreet. Laughter, the sun, and the crowd’s murmur create a positive vibe. Leaning against a brick wall, I felt every gram of that positivity, though that was likely due to a woman named Jaki, the prettiest woman in town.

The festival crowd was predominantly women, which came as no shock given Eckhart’s status as a Hollywood sex symbol. You may remember him from such films as: Thank You For Smoking; I, Frankenstein; The Core; or Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, in which he played Harvey Dent/Two-Face.

What did come as a surprise, though, was the depth of affection; I had no idea how important Eckhart was to American women. Most attendees went as far as dressing in old-timey aviator costumes (leather jacket and cap, goggles and scarf) as some kind of homage to the film Sully, in which Eckhart played Tom Hanks’ copilot.

That costume is what first caused me to notice Jaki. She was bent over, retrieving a model biplane a young girl had dropped. Her beige pants were so stretched her underwear showed. She then hinged upright (in slow motion), twirled her hat flaps, and squinted through her goggles my way. Nothing else mattered after that.

I knew instantly the surgeon was right: if I could sleep with Jaki then life would make sense again; life itself would be redeemed. So I marched over, introduced myself, and soon we were caught in the subtle dance known as flirtation. I employed the playful arm touch, the coy wink. Every word and detail must be subtle when flirting.

‘We should “talk” about Eckhart in the backseat of my car,’ I said.

Jaki blushed and wrapped her arms tight around my waist. The mariachi band entered a medley of Learning to Fly by the Foo Fighters and Fly Away by Lenny Kravitz. My glorious plan was working, and I would have gotten away with it too if it weren't for her meddling family...

Her mother—the cockblocker—materialised first. ‘We’re going to see Eckhart’s childhood home,’ she said. ‘My second son’s third daughter—my granddaughter—has never seen it, and she dreams of being a pilot.’

‘A pilot—like in Sully,’ I said. ‘We all agree Sully is a great film. Now, if you’ll excuse us.’

‘Her eyesight’s not so good though. She takes after her father there. He’s an accountant. I was never very good with numbers myself, though my husband was very quick. But he… he just loved hang gliding—loved it too much...’

The memory of her late husband colliding with a mountain caused her to cry. I assured her he would always be remembered, and corralled her into the embrace of another older woman who was also crying; the dead man in question was her brother. ‘The hang glider,’ they both wailed. ‘Too much wind!’

‘Wind, yes—a tragedy,’ I said. ‘Anyway, I really need to “talk” to your daughter about my condoms.’

After the mother and dead husband’s sister came Aunt Edna and the annoying niece.

Aunt Edna stabbed her walking-frame by my side and rubbed my bicep. ‘It’s so wonderful to see a man celebrate Eckhart’s legacy,’ she said, ‘and such a strong man too.’ The little girl, not to be outdone, wrapped around Jaki’s leg like a tamed rodent. The pair formed a strong offensive line; sacking the quarterback was becoming an even greater challenge. A new plan was needed, one with more charm and wit.

So, I crouched before the little girl and asked: ‘Would you like to see my impression of Eckhart?’

I admit I was tunnel-visioned. I only wanted to make Jaki laugh and moan. Nothing else mattered. I wanted her and it felt like years had passed since I wanted anyone. She was desire itself, resurrected. Anything was possible, all things were in order, the universe and life itself made sense; that’s how she made me feel. And, yes, my focus on sleeping with her was myopic, and did cause me to miss some important details (discussed below), but it came from a good place: love. It was love that made me think: do the impression, dazzle them all, the family will leave happy, and then you can fuck Jaki in the car or behind Rico’s Taco Stand.

It was Aunt Edna that proclaimed to the festival I was performing an Eckhart impression, and soon a crowd formed. A ring—no, a cage—of women dressed in leather jackets encircled me and the young girl.

‘This handsome man came here on a plane,’ Edna said to the newcomers. ‘Think about that, Ladies.’

‘Yes, Sully is a wonderful film.’ I said, matching her preacher’s tone. ‘Now if you don't mind, Edna.’

Edna apologised; the crowd quietened; the band stopped. Time for the impression.

There’s only one thing I wish I knew prior, one little detail: I wish I realised the festival was not celebrating Aaron Eckhart at all, but rather the aviator and feminist icon Amelia Earhart. Armed with that knowledge I might have avoided doing my Two-Face impression entirely, or at least not gone quite so hard.

First, the set up: left palm covers half the face–tick; right hand clamps the girl’s shoulder—tick, bulbous head moves so close the girl witnesses an eclipse—tick. Next: the girl trembles like Commissioner Gordan’s family when Two-Face threatens to kill them—tick. Finally, the impression itself: using enough volume to be heard even if the girl cups her ears on the Colorado state line, scream, ‘I’m gonna fucking kill you, Batman. Flip a fucking coin, you Bitch!’ Tick—impression over, time to fuck Jaki by Rico’s empty lard buckets in the name of love.

Unfortunately, my impression was poorly received. I didn’t appreciate how poorly though, until after a short sprint, when I was left panting and cowering inside the Mustang, terrified, as cabbage heads pelted the rear window.

People lament online trolls, but real-life critics remain the worst. I'll take a few nasty comments over a dozen bloodthirsty aviators rocking my car any day; online trolls cannot violate a car rental agreement.

The critics’ review ended in dramatic fashion, too. Jaki’s mother, one of the more vocal critics, crunched the driver-side window so hard the glass cracked. Many called it the cleanest right hook Kansas had ever seen, so clean, in fact, that the following year embroidered quilts depicting the punch were sold, with the caption: ‘Earhart Approved.’

After Jaki’s mother cleared the shattered glass with her elbow, she reached for the key. That’s when I put my foot down, and together we tackled the main street. We steamrolled the mariachi band’s stage and instruments, destroying everything, before finally, Jaki’s mother whipped off at the turn, rolled into a rose garden, emerged straight away, and began a foot chase. The last thing she heard before the Mustang roar carried me away was, ‘Sully sucked,’ because the truth is I’m a really, really slow learner.

6 - The Missouri River

I’m such a slow learner, in fact, that it took me visiting what I still believed was the Aaron Eckhart Museum to learn the truth. Full of hurt pride, my intention was to run the Two-Face impression on a fresh audience; but then I read the sign: The Amelia Earhart Museum.

The museum was Earhart’s childhood home. It overlooked the surrounding plains of the Missouri River, and on the muddy bank of that mighty river—using the Viagra bag as a seat—I sat and reflected.

That part of Atchison was peaceful, breathtaking in fact: the way light-beams shine on the riverbank, the broad sky... I could see how it inspired a young Earhart to soar, to dream. It certainly helped my thoughts to drift, and sitting with the river’s flow, those thoughts soon drifted to Jaki.

Before my impression, Jaki’s face was soft and angelic, but afterwards her squished brow and wrinkled chin were ugly to me. Joy is so much more attractive than disappointment, disgust. So, what was once beautiful had been soured, and by who: by me, my actions, my stupidity, my self-centeredness. Is that my legacy, I wondered? Am I a weed ruining life’s garden? Me and my easy life, how rotten.

Thoughts of this ilk scurried for a seat in my mind as though the music had stopped. It was time to drown them out once and for all, so I waded into the mighty Missouri.

Under my left arm, I clasped the Viagra bag. Under my right, I held the Condom bag. I nestled my bare feet into the riverbed to fight the current, and then turned to the sky. I needed to speak with Earhart. ‘Hear me, Ghost of Earhart, for I summon you...’

Despite being summer, the Missouri River was cold, though it didn’t bother me. I talked fast and free with Amelia Earhart until my fingers pruned and my balls shrunk.

‘Over the last five years,’ I said somewhere in that monologue, ‘I’ve been trying to give up, and that process is causing me to behave in erratic ways.’ The sky—her ghost—quietly listened. ‘I don’t mean suicide but a state of terminal apathy. I want to be the guy in the office who, when confronted with some soul-crushing process, just says, “it is what it is.” I want to be the relative who was never there, but at the funeral says, “I should have been there,” and then the next day forgets it entirely. I want to let work get in the way. I want someone else to blame for my health. But I’m not that guy. My soul is in a constant state of agitation.’

I talked in this rambling manner until my thoughts turned dark. ‘All this futility, Amelia, has changed me. Take the woman in the hostel, for example. For years I tried to reconcile the friction between compassion and order. As a younger man, I was quick to spout the line, “But what socio-economic factors led x to smash the liquor store employee with a bottle?” I was quick to say things like, “We need more support programs to prevent this behaviour.” True, but incomplete. Programs are never 100% effective, and they take years—decades—to work, if ever. People also have a right to safety now. Jails and asylums are not only to rehabilitate and punish; they are to quarantine. Order is important. We should help, yes, but we must also protect. Two things can be true at the same time, but compassion seems to demand a castration of sense. Like when I was fourteen, and I was attacked from behind by a homeless drug addict. I heard his orgasm, turned, and saw he had not yet lowered his pants; the attack was premature. Afterwards, we stared at one another. “He has lived a hard life,” I told myself. My compassion crowded out my own self-preservation, you see. But that’s how people talk; you mention a problem, and they say, “But what led x to…” They don’t give the anger any air—but it’s there, it’s real. And each kneejerk call for compassion works to invalidate the anger, and over time the invalidations work to erode the compassion. Ironically, all that remains is hate—’

I stopped. I realised I was in a river with two bags under my arms. ‘Sorry about that, Ghost of Earhart,’ I said. ‘My mind is like the flow of urine: it can be hard to stop.’

I returned to the task at hand. I swivelled to face downstream. The town was on my right and the grey bridge was ahead. The water sang its constant song.

‘Amelia,’ I said, ‘I formally—and without reservation—give up. I no longer care what happens to this world or the people in it—me included. Caring has only caused me to hate, and hating has only caused me to harm. So, let the waters of the Missouri swallow my precious load just as the Pacific swallowed you. Take my sacrifice, I beg thee, and if this be the right decision, I pray that you send me a sign.’

I released the condom bag like some mythical infant of old and did the same for the second bag. The twin bundles bobbed downstream and out of my life.

That’s how I lost all my condoms in Atcheson.

When the bags followed the riverbend out of sight, the sign came: a biplane shot through the clouds, twirled like a ribbon in the blue, and disappeared into another cloud-bed. A panel of light warmed my wet face then, and my heart throbbed intensely. ‘Thank you, Ms Earhart,’ I said and exited the waters, a new man.

By ‘new man’ I mean specifically that I had the firmest erection of my life—hard as a light-pole.

I attributed the excitement to Amelia Earhart’s blessing, but in hindsight the six Viagra I swallowed while on the riverbank were the likely cause.

Why I had an erection did not matter, though, to the Channel 5 News crew set up on the bank. They were interviewing families on the hill where Earhart played as a girl.

Completely unaware, I exited the river—arms wide, head back, penis firm. The cameraman turned the lens on me just as the mothers gasped. Thankfully, the erection pressing through my soaked pants was blurred on the evening news, though Customs and Border Protection officers Bourke, Miller and Ramirez, still probably shared a laugh. What did go unedited, however, was the audio: I tried to explain myself to the screaming mothers, they didn’t buy it, and I gave up. I didn’t care—at all.

‘Oh, this,’ I said to the families. ‘This isn’t for you; a dead woman gave me this.’

FOREIGN NECROPHILIAC TERRORIZES ANNUAL AMELIA EARHART FESTIVAL

7 - Melbourne

After Atcheson, I spent five wonderful days with my brother and his wife in Minnesota, and had a quick stop in Boulder, Colorado, before returning home. Seeing my brother was great, but it was so quick—like a dream—and before I knew it I was back at Cabrini Hospital in Melbourne.

The surgeon wanted to discuss follow-up investigations, life-style changes, etc. Mostly, he wanted to rule out cancer. I knew a colonoscopy had to be scheduled and I suspected I would walk into his office to find him with a flashlight and some tongs.

While waiting to see the surgeon, I talked to the old man opposite me. We were the only two in the beige waiting room on our own. Everyone else had coupled up.

He was a pale old fella, with copper through his remaining hair. He wore an old t-shirt, and it fit him like a bag because he was dying from cancer and losing so much weight. He told me the shirt used to be skin-tight. ‘I was a physical specimen,’ he kept saying. ‘A district-level cricketer.’

We ended up waiting for such a long time that I basically told him everything I’ve said so far. He laughed at the points I intended to be funny and shot me the odd serious glance at the raw bits. ‘So, that’s it,’ he said at the end of my story, ‘you gave up.’

‘I suppose, yeah. My gut no longer hurts. I don’t lose myself to thought. I just—’

‘Live,’ he said, cutting me off, ‘or exist.’

‘That’s right—exist, a fine word.’

‘Easier that way, I suppose...’

I nodded. I liked talking to the old fella; he seemed to get it, seemed to get me.

The reception appeared in the doorway. ‘Mr Luke Skelton,’ she said, ‘the doctor will kill you now.’

‘That’s me,’ I said to the old man.

When I stood up, he pushed on the armrests and rose to his feet. ‘Pleasure talking to you,’ he said.

‘Likewise.’ We shook hands and I turned towards the office to learn my fate.

About two paces from the door, though, there was a smash.

The old man had taken the terracotta pot from the side table next to where we sat and smashed it on the carpet. At his feet was an incriminating dirt pile with the corpse of a fake plant in the centre. He was wiping saliva from the corners of his mouth, his eyes looked possessed. The other patients and their support shifted their gaze from him to me, and back again.

‘Look at the damned plant,’ he said. ‘I said, “Look at the fucking plant.”’

I lowered my gaze to the mess on the floor.

‘Only fake flowers never wilt,’ he said. ‘Rigid and green they may be, but they never live. You wilted—so what? That’s it—you’re done. You give in. You quit. That’s all you’ve got. You feel lonely, useless, confused, rotten—so what? That’s part of being a feeling thing. You’re fully alive, damn it. You feel it all, so feel it. Don’t understand what’s happening, can’t see the future, scared—so what? Are you not up to the task? Can you not handle a stiff breeze? Listen to me: Don’t you quit. Don’t you give in. Don’t you yield. Don’t you fold. Don’t you take a backwards fucking step. There’s something out there for you, I know it. You keep searching. You keep moving and follow your heart. Listen to your heart because this is it. Don’t turn cold. You’re in the fucking shit—right now. But you can do it, I know you can, because your heart feels and your mind ticks. You are fully alive. Don’t throw that away, for anything, least of all “to exist.” There’s someone out there who will need you to show up one day as you are. So never give up—ever. Play hard to the fucking siren. To the siren, okay?’

In that moment, whatever this holiday was—this vacation from purpose—ended. If all I do in my life is remember those words, live in accordance with them, and pass them on to those in need—at the right time—then that would be a life not wasted.

‘You have my word,’ I said to the old man. ‘To the siren.’

Really late to the party here, but I really liked this one too.

Some notes:

>The Aaron Eckhart switcheroo really got me, should've seen that coming.

>Chris Hansen of all people showing up also got me.

>Love the Scooby reference you threw in with the meddling family.

>That monologue about compassion leading to a castration of anger was too real.

>That final monologue by that old man helped balance the tone a lot. It could've easily felt sappy or just tacked-on, but it didn't, at least to me. I'd be proud of that.

>You decided to name the protagonist after your own name. Why though?

>This one was pretty lengthy; how much stuff was left on the cutting floor? Do you feel like you could've cut more? Or are you happy with it now as it is?

Echoing everyone else here, but yeah, it was nice reading this. Keep it up, Luke!

Like if John Swartzwelder teamed up with Jack Kerouac to write a sequel to On The Road, but starring Tobias Fünke. But 100% authentic Luke Skelton. As always, I found the moving parts moving and the funny parts funny - just like the sage old man at the end. It was not lost on me that the person capable of giving solid advice was a District Wicket Keeper.

"online trolls cannot violate a car rental agreement" really made me laugh for some reason.

Another great story, I enjoyed reading it.