Link to the story

Overview

Thank you for reading my story, Redemption in America.

Redemption in America is a fictional account of a recent trip to America to visit my brother in Minnesota. Genre-wise, it was influenced by Norm Macdonald’s ‘memoir,’ Based on a True Story. To quote Norm from an interview with Larry King, ‘It’s not facts, but it’s true.’

Through this story, I was trying to document—and work through—my last few months/years. As is often the case, the actual events matter less than the perspective from which we experience them. Two people can have similar days, but they can mean different things. Even the same person can have similar days and experience them differently: if they have matured, been hurt, are stressed, etc.

I left for America in a state of poor physical health with quite a lot of anger, frustration, and loneliness, and, as absurd as this story is, it’s an attempt to ask, ‘Well, why? What’s going on? Should I sell your helmet and find a tall bridge?’

More broadly, I don’t think I’m alone in feeling doubt and confusion right now, so I wrote the story in the hopes others might relate. That’s one of the ironies of writing, or any art: by expressing your loneliness you feel connected with others.

You feel lonely, misunderstood, judged, and there’s no life purpose to soften your fall, so you fall hard. You feel anger, resentment, and frustration at the world’s judgement. You feel guilt for your poor reaction to the world. You become exasperated; the old ways of coping stop working. You can’t do it that way forever. You grow tired and forlorn. Untangling that mess feels like clearing chewing gum from your hair. If that in anyway describes where you’re at, then read the story, laugh at my foolishness.

Technique

By way of writing technique, I proactively worked on the following elements:

Character

Handling a bigger cast of characters

Writing interesting dialogue

Pacing

Controlling pacing through different levels of action

Controlling pacing through structure variety

Prose

Tighter prose through sentence structure

New imagery

Process

Thematic grounding of the story

Adding more tangents to the recipe

Following my nose

Character

I tried to bring the world alive by adding more characters, making those characters interesting, and providing them with interesting dialogue. During editing, I revised the characters to make them more. Examples include:

The surgeon dressed as Austin Powers with accidentally terrible bedside manner

The dying senile man who curses himself

The scary Customs and Border Protection officers

The homeless man with a knife in his anus

The old wise lady in the gas station (she was real, by the way).

Jaki’s family at the festival

I haven’t—and won’t—do an analysis, but I think this story is 2-3x longer than most I write but has 5x the number of characters. In terms of how I used the characters, they were a reflection of the protagonist’s state. The dying man, for example, telling his son he was never good enough but mistakenly using his own name, was close to how the protagonist felt in hospital.

By way of dialogue, I tried to imagine interesting things a character could say in their responses. The obvious response was the only thing not allowed. My favourite example is from the airport scene where the CBP offer goes:

‘Says on your form you’re visiting your brother in Minnesota,’ she continued.

‘He’s innocent.’

I thought that was pretty nifty.

Pacing

You can make something move faster by focusing on the action: she spoke, she opened the door, she fled… A reader’s mind can follow action quite naturally in way it can’t with abstract concepts. But ‘action’ can be viewed on so many different levels.

A single atom moved.

His motor neurons sent a signal to the brain causing the quad muscle to flex

He took a step forward with his right leg

He walked to the end of the block, past the bakery

He walked across the entire town

When he lived in New York, he often walked across town

In his forties, he was an avid walker

Abigail’s biggest lesson from her father who died was the joy of walking

Humans in the twentieth century lived in tight cities and often walked

Humans were bipedal creatures capable of walking

Life, in some random expressions, included movement

Everything.

When writing a story, it’s a choice whether to say John and Susan had a nasty conversation or to write out the dialogue. Or to just say John and Susan argued a lot during their marriage… And the same choices are required for abstract concepts, jokes, side quests, etc. Each variable has a multitude of levels, and each requires a choice. That choice is informed by a set of principles, tastes, and predispositions (often unknown), though one is usually brevity: How does it affect the pace?

In this story, I tried to control pacing (make it move fast and effortlessly) in a few ways:

Remove duplication. In the interrogation room, the protagonist rambles his explanation. In the draft, there was a second rambled explanation to the man pushing his wheelchair. But I thought, we’ve done that already; it will be boring.

Remove characters. I deleted the cabbie that drove the protagonist to the hostel. He felt superfluous given there was already a zany character in the scene. I thought of a zaniness dial and felt it was too high with both characters.

Various levels. I mixed blow-by-blow scenes with flyover sections (levels, say, 3 and 5 above). The hospital was two images. The interrogation room was blow-by-blow. From Dallas to Kansas, was short 1-2 paragraph vignettes. Atcheson was blow-by-blow. The mix kept it interesting, I hope.

Concrete details. I tried to always have at least one real, tangible moment for each bit: a line of dialogue, a character action, something to tether the story to as the hurricane of tangents, odd characters and absurd details blows through.

Pacing is still under construction. I’m curious how exactly to blend abstractions and concrete details to control pace. The word that comes to mind is intent. What is my intent? At one moment I want you to see a flash of a room, a house, a woman. Next, an abstraction of that person: her archetype, perhaps. Then a concept: loneliness. Then a detail: a TV advert for life insurance. Do I mix them, weave them, or keep them clean? Do you serve them like a three-course meal in chronological order, or do you plug in the blender? Some writers go one way, some another. I’m not sure where I land yet.

Prose

Does it read well?

Style and voice are constant considerations. Of the books I’ve read this year, Saul Bellow’s Herzog is the most inspirational from a prose perspective. He has the ability to just say whatever he likes and make it work, like a jazz musician who can use any note in any key. I don’t know how he does it, but that’s the goal: freedom.

So each story I try to push it a little. The end of each sentence is an opportunity to go a variety of places. I try and take the interesting route where I am able. Like a footballer in practice, you can go down the line or you can try for that 45-degree kick. The good players can do both. My best attempt from this story, I think, was the senile man. I shifted from a description of his senility to an example of it, then to his death:

The old man was cancerous and senile. He spent the last two days on loudspeaker yelling at his son, reciting the same dog-eared script: ‘John, you weren’t good enough.’ ‘Dad, my name is Jared. You are John, remember?’ ‘Never good enough, John—a disappointment.’ But come nightfall, he called only for God. And for some—John included—death is orgasmic: an overwhelming bodily sensation. He gripped the bedsheets and moaned at his end. He climbed like a skeleton from the dirt one last time and expired. His soul left. His body, however, floated in the sparkling cosmos of warning lights and monitors.

Tense

In this story, I toyed with tense a bit more to try and reduce clunky phrasing like ‘has been’ and ‘had been’ or ‘will have been’ or ‘was being.’ They are ugly, sometimes necessary, sure, but sometimes just ugly. There’s usually a way around it.

Michael Kaplan calls it ‘overuse of the conditional or past perfect verb tense.’ He suggests the below edits, the point being you can change tenses to make it read better. Here it shifts after the first sentence. As Kaplan says, ‘Strict grammatical tense agreement is a wonderful thing, but agreeable prose is even better.’

Every morning that summer, John had gotten up around six. He

hadsmelled the bacon and pancakes his motherhad madewas making in the kitchen, and his stomachhad givengave a little hungry flip. Hehadjumped out of bed andhadrushed to the bathroom. The tile floorhad beenwas cool against his bare feet. Hehadquickly washed his facequickly.

I’m also trying to not use ‘then’ where I can. It is often implied. The man picked up the phone and then said ‘hello’ does not require the word then in it, for example.

Imagery

A visual image assists the reader’s thought. George Orwell explained it best in his essay Politics and the English Language:

A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically ‘dead’ (e. g. iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgels for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed.

So, instead of using cliche and tired metaphors and similes, I came up with new ones. Not only does this, hopefully, help the reader to better understand the text, but it also forces me to engage more with the writing process, which is really a thought process.

Below is Orwell explaining the state of the English language and its tired images:

The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not. This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose, and especially of any kind of political writing. As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.

Process

I tried to ground the story through theme. Most of my stories orbit the idea that (1) we are going to die, (2) life is short and precious, (3) it’s unclear what to do while we’re alive, (4) even more so in a crazy, accelerated, technological society, however, (5) accepting the madness or moulding to it also seems to be a bad strategy, and (6) how to respond is a matter of urgent discussion, collectively.

The protagonist’s health concerns, and internal thoughts helped to ground this story in that theme/space. Moving forward, I would like to make this theme more obvious. What are we supposed to do with our lives, noting we will die? Is almost always the central question, explored through people not doing it well.

This time around, I indulged a little more in tangents/side quests. The stuff around consulting was not forcefully moving the plot, but I felt it explained the madness as I see it, which is one of the complicating factors of the questions around what to do.

And, finally, I followed my nose and gut. ‘Haecceity’ aka ‘thisness,’ is something I’m trying to develop. I want people to read something I’ve written and know I wrote it. Ideally, they also enjoy the piece and find it stimulating, but it first needs to be me.

Thank you

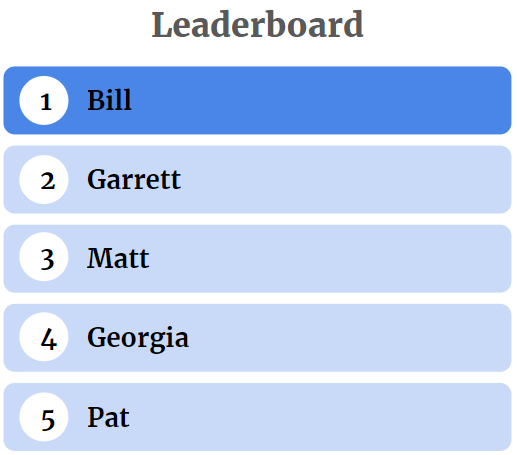

Thanks to everyone for the continued supports. Thanks specifically to the five people below who have supported me the most financially through buymeacoffee.com

I think it's great that you put so much thought into this, and even greater you posted it for everyone. A few thoughts: 1) funny how some of the sayings Orwell put forth as tired examples don't seem that way, to me, anymore. Others I've never even heard of. 2) I've scoured my short story, removing half my "then" on your advice. A+ 3) I heartily recommend "Editing Fiction at Sentence Level" by Louise Harnby